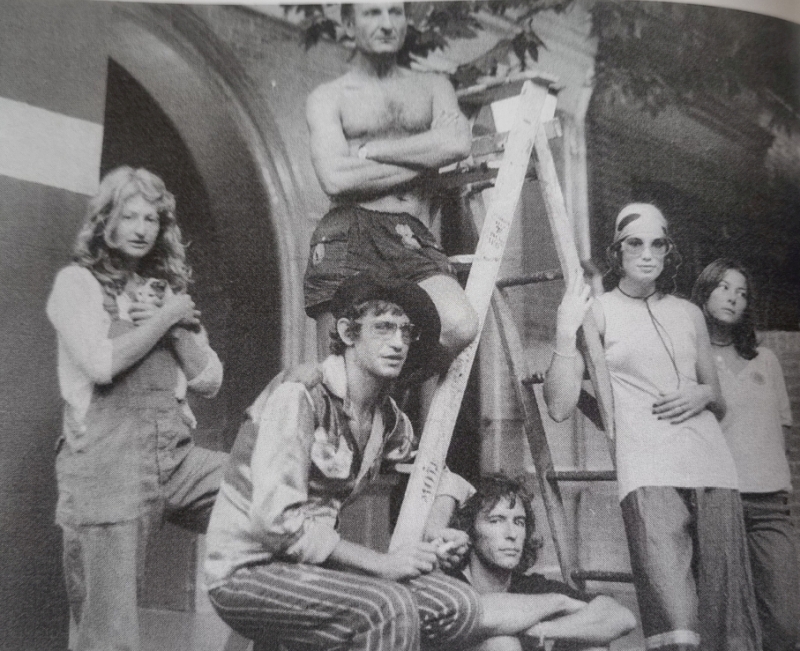

Martin Sharp posed with a group of friends for a newspaper photo on the eve of a landmark Yellow House exhibition opening in Sydney on April Fool’s Day 1971.

At the time, those gathered around him were described only as Sharp’s friends. When I used the image in my biography, I could identify only the extraordinary David Litvinoff, muscle-bound and bare-chested, standing on the ladder above Martin.

Now Martin’s cousin Andrew Sharp, a Yellow House habitué, has filled in most of the blanks. Pictured from left are: Colette St John, Martin Sharp, David Litvinoff, Dick Weight & Victoria Cobden. The young woman on the right remains a mystery.

The Australian’s article related how the Yellow House, in Macleay Street, had been inspired by Van Gogh’s failed attempt to establish a community of artists in the south of France.

‘It didn’t work, but it might now,’ Martin said.

The photo was taken ahead of the opening of The Incredible Shrinking Exhibition in which Martin shrank a collection of his collages and other works to a fraction of their original size.

Martin met David Litvinoff in London. He was a raconteur and an East End rogue who moved between London’s art, pop and criminal worlds. Keith Richards described Litvinoff as: ‘On the borders of art and villainy.’ Litvinoff fuelled the myth that he was the inspiration for The Rolling Stones’ Jumpin’ Jack Flash.

Colette St John’s lawyer father, Edward St John, appeared in the Sydney Oz magazine obscenity appeal in the mid-sixties in which Martin and others had their jail sentences overturned.

Dick Weight was among the artists who transformed the rooms of the Yellow House into enchanting spaces. His brother Greg Weight photographed the interiors.

Victoria Cobden appeared in the original Sydney production of the musical Hair, directed by Jim Sharman.

The opening kicked off with a tap dance by Little Nell – who later shot to screen stardom as Columbia in The Rocky Horror Show.

After 40 years, it’s good to remember some of the friends who made the extraordinary exhibition happen.